In September, 2018, I had an opportunity to attend ArtsMidwest in Indianapolis. This was a large conference that featured different arts organizations, councils and artists from around the Midwest. As I was scanning the big expo hall filled with different artists and companies showing what they do for the potential of being hired, I couldn’t help but think how this was the perfect venue to promote world music. As I was half way through this hall I came upon Ronnie Malley, an exceptional world music artist that specializes performing the oud. We knew each other, but only through other musician friends and from watching each others videos online. We made such a great connection, it felt as if we were friends for several years.

Oudist Ronnie Malley has been playing music since he was a young child. His influence is no doubt due to his father playing Middle Eastern music. He had a group called Golden Nights Band and Ronnie used to enjoy watching his dad and his friends on stage entertaining audiences. So it should come to no surprise that at a young age Ronnie would be interested and influenced by his father to play music. His father formed a band that consisted of Ronnie and his brother. Throughout the public school system, Ronnie performed percussion but at the age of nine, he started to take guitar lessons. It was natural for Ronnie, as a percussionist and guitarist to want to play rock n’ roll music, but his father wanted to make sure his son expanded his horizon on music and focused on Middle Eastern and North African traditional music. This important time in Ronnie’s musical exposure with his father helped him appreciate the music of Arab, Armenian, Assyrian, Indian, North African, Greek, and Turkish music. “I saw a place in music to pour my passion and angst. It really became an obsession learning songs, especially songs of my heritage” said Malley.

Oudist Ronnie Malley has been playing music since he was a young child. His influence is no doubt due to his father playing Middle Eastern music. He had a group called Golden Nights Band and Ronnie used to enjoy watching his dad and his friends on stage entertaining audiences. So it should come to no surprise that at a young age Ronnie would be interested and influenced by his father to play music. His father formed a band that consisted of Ronnie and his brother. Throughout the public school system, Ronnie performed percussion but at the age of nine, he started to take guitar lessons. It was natural for Ronnie, as a percussionist and guitarist to want to play rock n’ roll music, but his father wanted to make sure his son expanded his horizon on music and focused on Middle Eastern and North African traditional music. This important time in Ronnie’s musical exposure with his father helped him appreciate the music of Arab, Armenian, Assyrian, Indian, North African, Greek, and Turkish music. “I saw a place in music to pour my passion and angst. It really became an obsession learning songs, especially songs of my heritage” said Malley.

When Ronnie was a teenager, his father insisted that he pick up the keyboard as it would give their ensemble a competitive advantage in the market of performing Middle Eastern music in the community. However, this wasn’t satisfying to Ronnie and when he turned 16, the oud became his main instrument in his life. “I felt weird playing Mid-Eastern music on instruments made in Japan and felt like I had to take up an instrument from my heritage”.

In 1992, Ronnie with his brother and famous Lebanese singer Tony Hanna after playing a show together.

Through his father and his father’s band, Ronnie learned invaluable lessons surrounding the modal system of Middle Eastern music. Makams, are sets of complex scales utilized in performing traditional Middle Eastern music. Trying to get a teenager that was listening to heavy metal rock in large amounts and at high large volume to appreciate the artistic traditions of Arabic music took a patient father. Ronnie recalls being allowed to play a cassette of heavy metal music in the car while riding with his dad. His dad listened to the entire album and appreciative of the fact that his son was a music enthusiast of any kind. However, when this heavy metal album was done, he put in a recording consisting of Abdel Halim Hafez, a legendary Egyptian singer, movie star and composer. Ronnie vividly recalls the song he heard was Mawood, and he was hooked to the music! “I remember hearing Omar Khorshid on guitar in the mix of a string orchestra, organ, qanoun, nay, and other Middle Eastern instruments. I wanted to consume anything and everything Egyptian and Levantine”.

My second meaningful musical experience happened five years later after hearing Abdel Halim Hafez. Serendipitously, it was a gig with Magdi Husseini, the keyboardist featured on Abdel Halim and Om Kalthoum’s albums. I was over the moon to think I was going to play with a legend who I listened to, and whose name I heard mentioned by Abdel Halim on live recordings. When the time can for the gig, the song he picked to feature was Mawood, the same piece that was my intro to Mid-Eastern music. During the concert, I played the guitar solo featured in the song and Magdi turned to me on stage and said, “Uh! Ya Ronnie Khorshid!” It was definitely a confidence boosting moment”.

Playing music can be compared to having a religious experience for Ronnie. “Music has long been a refuge for me from idleness and an outlet for my obsession with problem solving. Sometimes I wouldn’t leave my room for eight hours until I had down a piece of music I was working on. That practice paid off in the corporate world as well. It helped me learn to pay close attention to detail, be exacting, and learn how to pick up on patterns – skills useful in any profession. Today, I truly believe music is a way to speak in the absence of words. It is a spiritual practice that can bring people together and move them in ways that sometimes words cannot. I know every time I hit the stage, even as a kid, it was like a pulpit that had me sailing through the heavens”.

Preserving music has an important meaning to Ronnie and it speaks to his identity. “It helps us understand who we are, which can help us better explain to others who we are as well. Music and the arts in different global cultures are like their respective cuisines, they offer flavor, color, and can serve as a portal for learning about the richness of societies that can sometimes be ‘otherized.'”

Ronnie is again reminded of the contribution his father and his musicians made in shaping his philosophies and appreciation of music and life. “If it weren’t for my dad and his community of musical friends encouraging us to learn music, especially the music of my heritage, I wouldn’t be fluent in Arabic, I wouldn’t have played at Arab Christian churches (I grew up Muslim) to know the vastly diverse Mid-Eastern societies of various backgrounds and faiths, and more importantly, I wouldn’t have been as confident in my identity – Palestinian, Muslim, and Arab”.

No matter what you do in life, make sure you keep music as a part of it. Success is really determined on how much time one puts in. That includes time for practice, performing, and playing with others who are better than you because they will push to make you better. There are so many ways to work in the field of music, more than I imagined ever doing. I’ve had the opportunity to work as a studio session musician, composer for film and theater, accompanist, sound designer, theatrical performer, educator, and more. But even if one’s aspirations don’t take them into the professional world of music, it still has immense benefits. Music and art have an influence on a great deal of our cognition: how we speak, how we view the world, how we understand collaboration, attention to details, and having integrity in what we do. Art should never be viewed as an extra-curricular aspect to one’s life, but rather as an essential component to help with academic development, spiritual growth, and well-being.

No matter what you do in life, make sure you keep music as a part of it. Success is really determined on how much time one puts in. That includes time for practice, performing, and playing with others who are better than you because they will push to make you better. There are so many ways to work in the field of music, more than I imagined ever doing. I’ve had the opportunity to work as a studio session musician, composer for film and theater, accompanist, sound designer, theatrical performer, educator, and more. But even if one’s aspirations don’t take them into the professional world of music, it still has immense benefits. Music and art have an influence on a great deal of our cognition: how we speak, how we view the world, how we understand collaboration, attention to details, and having integrity in what we do. Art should never be viewed as an extra-curricular aspect to one’s life, but rather as an essential component to help with academic development, spiritual growth, and well-being.

Ronnie is a working musician with a diverse list of credits to his name. Most notably has been as a musician and consultant on Disney’s The Jungle Book (Goodman Theater, Huntington Theater).

In 2007, Ronnie, along with some fellow musicians, formed Intercultural Music Production which is a cultural arts organization committed to empowering a global community through performance, education, and production. Working with Middle Eastern and World Music artists, this organization has worked with children in the Chicago, Illinois and suburban school districts, local and national colleges and universities, consulates, intercultural/interfaith groups, as well as with international arts organizations and artists.

For more information about Ronnie and his music, please visit his website.

Harry started playing music at the age of 9 on the piano , eventually becoming classically trained. Growing up,

Harry started playing music at the age of 9 on the piano , eventually becoming classically trained. Growing up,

This was a plea from a man separated by a Genocide that systematically eliminated over a million and a half Armenians by order of the Turkish Ottoman Empire toward the end of World War I. This man took out an advertisement in one of the Armenian newspapers searching for his loved ones four years after a date that would change his life forever.

This was a plea from a man separated by a Genocide that systematically eliminated over a million and a half Armenians by order of the Turkish Ottoman Empire toward the end of World War I. This man took out an advertisement in one of the Armenian newspapers searching for his loved ones four years after a date that would change his life forever. It’s the anguish of this man who spent years searching for his loved ones and escaping the Armenian Genocide in hopes that one day he would be reunited with his sisters.

It’s the anguish of this man who spent years searching for his loved ones and escaping the Armenian Genocide in hopes that one day he would be reunited with his sisters.

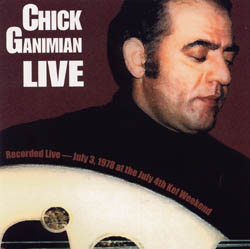

At a certain point I felt (as a record producer) that it would be great to pay homage to Chick by releasing some type of recording that featured his musicianship. As I mentioned earlier, he had few recordings ever released, but he was recorded live in different settings. Nightclub surroundings and festivals were Chick’s playground. In 1999, I released

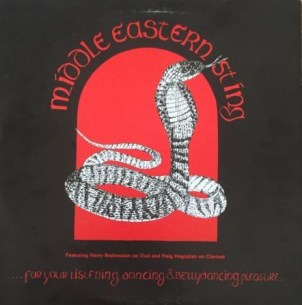

At a certain point I felt (as a record producer) that it would be great to pay homage to Chick by releasing some type of recording that featured his musicianship. As I mentioned earlier, he had few recordings ever released, but he was recorded live in different settings. Nightclub surroundings and festivals were Chick’s playground. In 1999, I released  “Let me confess that I’m biased about this unknown genius and his virtuosity on the oud. I was playing clarinet with him for years and played on this job. He was the finest musician for belly-dancers. If you like Middle Eastern music, you’ll love this CD” said in 2015 by the late Haig Hagopian referring to the release of this CD. As the record producer of this compilation, I must admit that it doesn’t provide the full breadth of Chick’s work but it does provide a good example of his playing abilities in front of a live audience with some of his signature songs such as Efem, Canakalle Icinde, and Halvaci Halva.

“Let me confess that I’m biased about this unknown genius and his virtuosity on the oud. I was playing clarinet with him for years and played on this job. He was the finest musician for belly-dancers. If you like Middle Eastern music, you’ll love this CD” said in 2015 by the late Haig Hagopian referring to the release of this CD. As the record producer of this compilation, I must admit that it doesn’t provide the full breadth of Chick’s work but it does provide a good example of his playing abilities in front of a live audience with some of his signature songs such as Efem, Canakalle Icinde, and Halvaci Halva.

He played the Green Grove Manor in Asbury Park, New Jersey for a decade as well as at Philharmonic Hall, Lincoln Center, and Town Hall in New York City. Kochak has been credited for his comedic talent, fine support with the dirbakee (Arabic tom-tom), and resurrecting the debke, native dance of the Middle East. He had long associations with Dean Martin and Danny Thomas (Thomas and Kochak are both of Lebanese extraction). For decades, as a maker and producer of records, not to mention live performances, he ruled the Brooklyn and to a lesser extent the New England “Mecca East” scenes. In the 1980s he played the percussion for Anthony Quinn in the Broadway production of “Zorba.” In the twenty-first century the Sheik has conducted musicians and dancers on stage at an Atlantic Avenue festival in Brooklyn.

He played the Green Grove Manor in Asbury Park, New Jersey for a decade as well as at Philharmonic Hall, Lincoln Center, and Town Hall in New York City. Kochak has been credited for his comedic talent, fine support with the dirbakee (Arabic tom-tom), and resurrecting the debke, native dance of the Middle East. He had long associations with Dean Martin and Danny Thomas (Thomas and Kochak are both of Lebanese extraction). For decades, as a maker and producer of records, not to mention live performances, he ruled the Brooklyn and to a lesser extent the New England “Mecca East” scenes. In the 1980s he played the percussion for Anthony Quinn in the Broadway production of “Zorba.” In the twenty-first century the Sheik has conducted musicians and dancers on stage at an Atlantic Avenue festival in Brooklyn.

“George Righellis was full of life, and full of music. He always light up the room whenever he performed. He loved both Greek and Armenian music, but told me once in an interview that he always gravitated more toward Armenian music. He was such an inspiration to so many of us, and he will be very much missed.” said

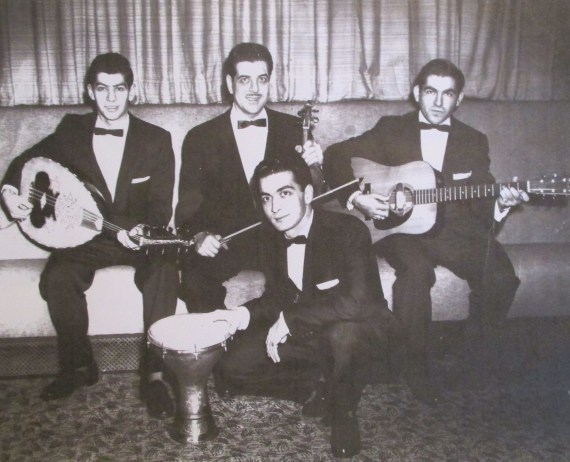

“George Righellis was full of life, and full of music. He always light up the room whenever he performed. He loved both Greek and Armenian music, but told me once in an interview that he always gravitated more toward Armenian music. He was such an inspiration to so many of us, and he will be very much missed.” said  “I have had many occasions to play music with George. All of them fun filled and musically rewarding. But although from Massachusetts, George represented a special place in the music of the New York City area as well, unbeknownst to him personally. George was the first musician that I heard using the guitar in our Armenian music back in the early 60s. I loved the sound that was created by the threesome Harry, Gary and George. (Harry Minassian, Gary Alexanian and George Righellis) in New England kef music. In 1962, and for the first time in New York, I started using the guitar in my group and in Armenian music. So the sound that George influenced in New England acted as a catalyst for me and for Armenian music in New York”. –

“I have had many occasions to play music with George. All of them fun filled and musically rewarding. But although from Massachusetts, George represented a special place in the music of the New York City area as well, unbeknownst to him personally. George was the first musician that I heard using the guitar in our Armenian music back in the early 60s. I loved the sound that was created by the threesome Harry, Gary and George. (Harry Minassian, Gary Alexanian and George Righellis) in New England kef music. In 1962, and for the first time in New York, I started using the guitar in my group and in Armenian music. So the sound that George influenced in New England acted as a catalyst for me and for Armenian music in New York”. –  “I first met George around 1970 — Eddie Mekjian produced two albums: Road to Harpoot and Greece after Sunset featuring George. I heard those albums and I was fascinated with the fullness of his guitar. Why was it so full from an acoustic guitar? The recording on that album stood out tremendously with the sound of George. I think he was the best guitarist for Armenian music and he blended perfectly with the bands. George was the first to introduce the guitar to Armenian music. The Armenian bands starting using guitar back in the 1950s by hiring Greek musicians. That’s why a lot of Armenian musicians have a extensive Greek repertoire in there material. The legacy George left is that he inspired a lot of the younger Armenian guitar players such as myself. I would copy every run and chord changes that he would do in a particular piece. I started playing with George at the Athenian Corner Restaurant in

“I first met George around 1970 — Eddie Mekjian produced two albums: Road to Harpoot and Greece after Sunset featuring George. I heard those albums and I was fascinated with the fullness of his guitar. Why was it so full from an acoustic guitar? The recording on that album stood out tremendously with the sound of George. I think he was the best guitarist for Armenian music and he blended perfectly with the bands. George was the first to introduce the guitar to Armenian music. The Armenian bands starting using guitar back in the 1950s by hiring Greek musicians. That’s why a lot of Armenian musicians have a extensive Greek repertoire in there material. The legacy George left is that he inspired a lot of the younger Armenian guitar players such as myself. I would copy every run and chord changes that he would do in a particular piece. I started playing with George at the Athenian Corner Restaurant in

It was inevitable

It was inevitable